Practically every piece of writing on the history of the pedal harp will quote the origins as being with Hochbrucker in 1720, and the harp housed in a museum in Vienna is held up as the proof-positive of this. For a long time, it was regarded as being the sole surviving example, but the emergence of other specimens has raised some serious questions about the Vienna instrument, and I would like to voice, and address these in this article.

I would like to point out that this is based on conjecture, interpretation, and observation, and is not intended to tear down a ‘sacred cow’ but to try and clarify some of the received wisdom we have about this instrument, and to encourage conversation and understanding of an instrument that is undeniably important in the history of the instrument.

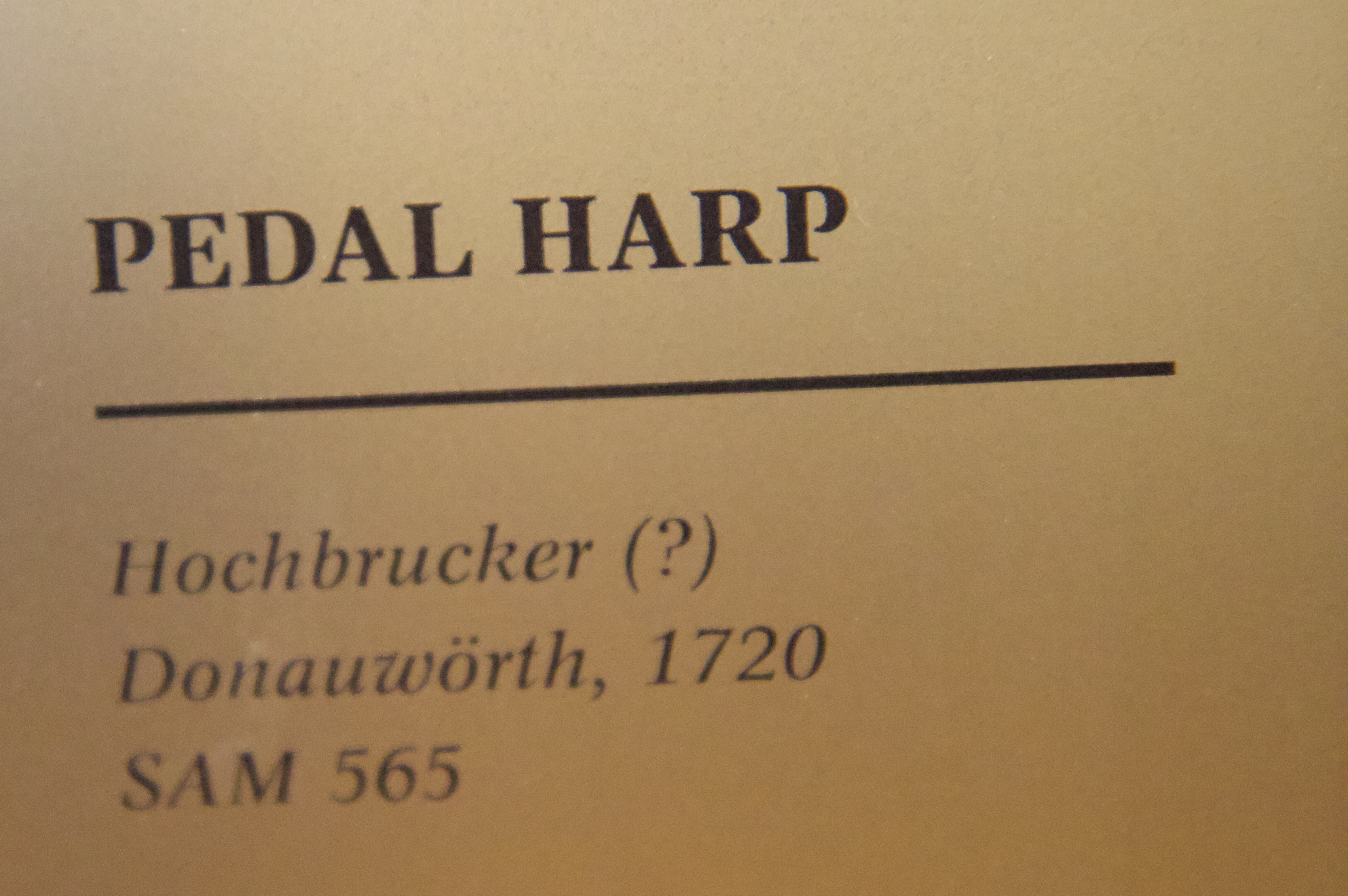

The instrument, catalogue no. SAM565 is on display, not as is generally cited, in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, but in the Weltmuseum, in a separate building, as part of the musical instrument collection. It sits in a glass case with two other 18th century pedal harps, and permission to examine it was declined on grounds of the fragility of the instrument. I do not intend to discuss the carved head currently mounted on the capital of the instrument. I do not believe it is original, and the image it represents is a whole article in its own right.

The instrument was examined by Beat Wolf in 2007, and a number of photographs made, and the museum maintains that further examination is unnecessary. I sent emails and a letter to Beat Wolf, asking to discuss the instrument, but received no response. Dr. Heike Fricke of the University of Leipzig was as generous as to share the notes and photographs made by Beat Wolf with me, which are now in their collection.

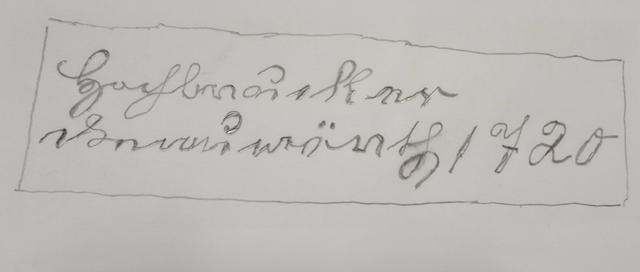

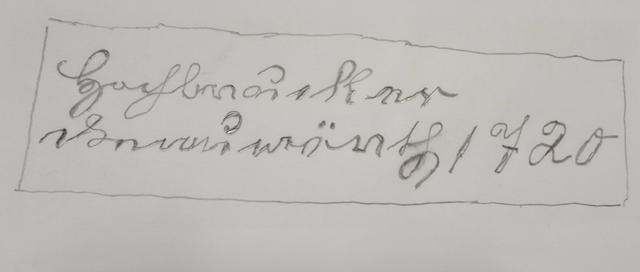

In these, we can see the two paper labels on the pedal box. One, handwritten and of some age, firmly glued into the void of the pedal box, clearly reads

Hochbrucker Donauworth 1720

The second is typed and lightly attached on the flat base of the pedal box, which states

Kunsthistoriches Museum

Sammlung alter Musikinstrumente

Inv-Nr, 565

Pedalharfe von Hochbrucker,

Donauwörth, 172

the whole has been over-stamped with an official museum stamp.

The label on the glass case is specific about the date and location of manufacture, but places a question mark after the attribution.

Looking for a source for the date quoted in the harp histories, we can find a number of sources.

WH Grattan-Flood's The Story of the Harp. (1905): We have seen in a previous chapter that the system of hooks or crooks, defective as it was, suggested further improvements in the mechanism of the harp. The most serious defect arose from the fact that whenever a semitone had to be formed, the left hand was temporarily lost to the performer when engaged on turning the hooks. However, the first decade of the 18th C passed over without any change. At length, about the year 1720, it fell to the lot of Herr Hochbrucker, a native of Dannauworth, in Bavaria to invent the pedal harp.

Hans Zingel, in volume IV of his Neue Harfenlehre also connects Hochbrucker, Dannauworth and 1720. He also refers to Hochbrucher’s “pedal harp, at first supplied with five, later with seven pedals...”

Grattan-Flood and Zingel are major figures in harp scholarship: they have been quoted by most of the writers of the twentieth century, and accepted so fully and completely that their statements have become lore, but neither gives a source for the information.

However, François-Joseph Fetis (1784–1871), in his Biographie Universelle des Musiciens (1837) lists four members of the Hochbrucker family and says that Hockbrucker (no first name given, but probably Jakob) invented the pedal harp about 1696, but did not make it public until 1720, and that his harp had pedals for C, D, F, G and B, but does not give a pedal order.

This is corroborated by the preface to an edition of arriettes, Opus II by Mr. Hochbrucker, in which he states that his father had been engaged in developing the pedal harp since 1697. This collection was published in Paris, and the Bibliothèque nationale de France identifies publication as 1769. Which Mr. Hochbrucker made the edition 0-is a matter of debate, but that is not the subject of this article. This preface is available on the web here.

Three surviving pedal harps

It would seem that having an instrument dated 1720 corroborates this, but there are three more pedal harps attributed to Hochbrucker survive, and the similarities and differences between the specimens raise a number of questions.

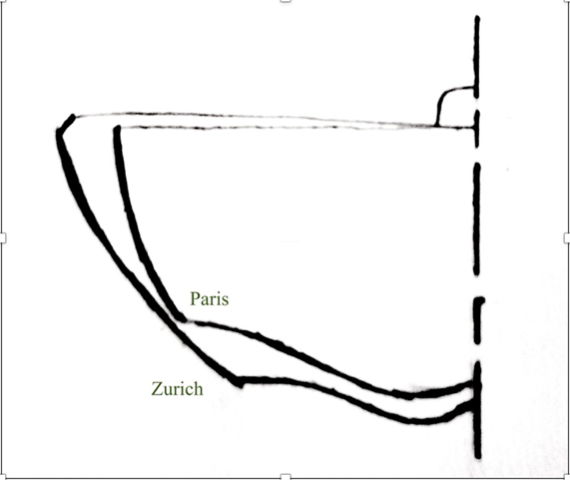

The instrument E.2009.1.1, housed at Citie de la Musique in Paris has a number of similarities. The neck, pillar and mechanism certainly could be from the same workshop. The body however, is very different.

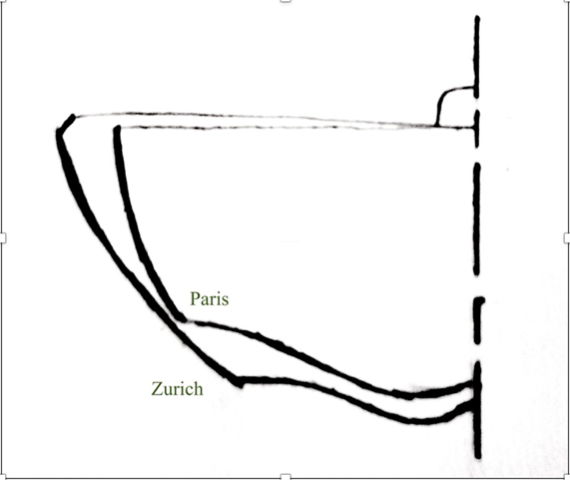

The second specimen is in the Bellerive Museum, Zürich, catalogue no. 1963-60 23. I have not been able to examine this harp, but superficial viewing of the photographs indicate that it is credibly from the same workshop as the Paris instrument.

The third instrument was in the possession of harp maker Rainer Thurau, and which I believe in now housed in the Musical Instrument Museum, Phoenix, Arizona. Although not identical to the Paris instrument, they also look very much to be the products of the same workshop.

All three of these have a shallow, narrow body, with a back made in four parts creating a series of curves. The Vienna instrument has a back made in seven staves, and is relatively wide in the bass.

All four instruments have a ‘flange’ mechanism, in which an arm attached to a rotating axle pushes the string against a small rod called a ‘baron.’

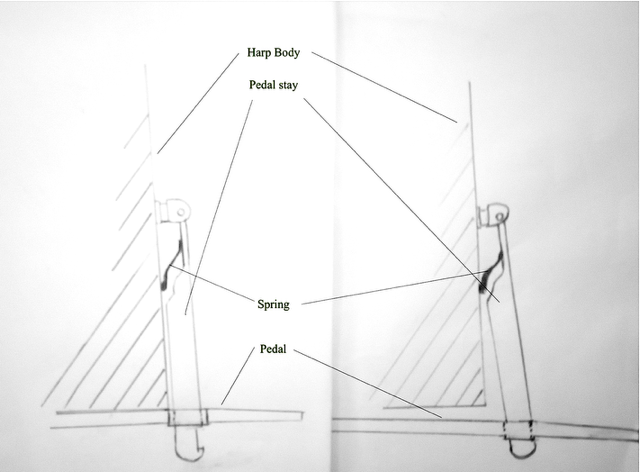

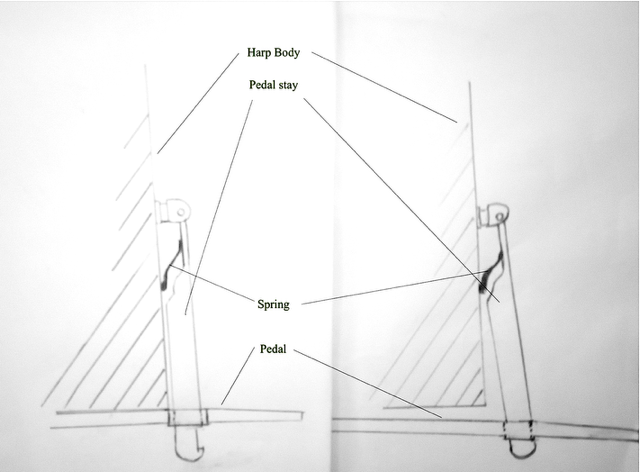

Whilst the Vienna instrument has a cross grain board, the three others have vertical grain quarter-sawn softwood. The Vienna instrument has a pedal box, which the others lack, and the pedals latch under the bottom block in cut ‘gates’ whilst the other three have sprung, external pedal stays that lock the pedal vertically, without any horizontal shift, and that need to be pushed in towards the body of the harp by the player to release the pedal.

The Vienna instrument has iron pedal arms with folding brass pedal treads. The other instruments have short iron pedals, with no added tread, and with a pierced slot through which the pedal-stay runs.

Dr. Beatrix Darmstädter, curator of the Vienna collection, at the time of enquiry, informs me that three pedals have been replaced, but has not identified which are the replacements. She also states that the pedal box is a later addition, but does not supply a date for the addition. Sebastian Kirsch informs me that the museum obtained the harp in 1943, but no information is offered about the condition on the instrument on accession, or where it was obtained.

It is also notable that on the Zurich and Paris instruments, the pedals appear to be attached to the bottom block by a screw though a spatulate spring. As there is no need of horizontal movement, the vertical engagement of the pedal is made by the pedal limb itself flexing at the spatulate end, obviating the need for a hinge or pivot. On the Vienna instrument the pedal limbs are morticed and a separate piece of metal is inserted which does not look as if it would flex, so whilst the horizontal motion of the pedal can be made using the attaching screw as the pivot point, it is difficult to see how the vertical motion to engage the mechanism is made. It may be that there is some motion afforded by a little slack in the screw itself, but without examination, it is not possible to see how the pedal can be moved.

The three vertical grain boards are undecorated, whilst the Vienna instrument has ‘edging’ of a delicate gold border in a flower and leaf design.

So where does this leave us?

Well, I accept that the harps were made in the same workshop at around the same time. It is impossible to project a timeline of manufacture, as the only definite date that I am aware of is 1728 on the mechanism of the Paris instrument.

I believe, though, that the Vienna instrument was rebuilt at some stage in its playing life, and that the body was made in the French manner, like the more typical harps of the later 18th century.

I repeat that this is pure conjecture, but if the Vienna body is original, why would later instruments from the same workshop revert to an earlier form of construction (the vertical grain board) and the more restricted width of the narrow bodies?

A rough drawing of the sections of the bottom blocks fo the Paris and Zurich instruments

For the latter, there could be any number of possible explanations. The Vienna instrument has had two triangular fillets added inside the board, bracing the tenor and bass ranges, and seems to lack an internal string bar It is possible that the harp was made, strung, and found to have too much ‘rise’ on the board under tension, so later instruments were made differently to avoid this. This feels unlikely, though, and a more logical process would be that the French-style body was made, replacing the German-style original, and then found to be too lightly built, and braced to keep it playing, which raises questions regarding when would this have been done.

It would be interesting to measure the distances from the fixed bridge pins to the barons to determine how viable the semitone width is, and if it would be possible to regulate the Vienna harp as it stands.

Looking at the shoulder of the instrument, there are issues regarding how the back of the neck curve fits the box.

Firstly, the plate that covers the void in the neck where the mechanism sits doesn’t seem to fit the curve of the shoulder very well. A part of the ribs/top block of the body are visible where the block is not covered by the neck.

The facets of the staved body and clear until the top few inches when they are rather rounded over to make the polygonal body match the curved shoulder.

I would suggest that, along with the horizontal grain soundboard, this could imply that the body is a later replacement, which would leave us with a question regarding when this was done.

The horizontal grain of the soundboard is more in keeping with instruments post 1750-60, as are folding pedal treads, which would lead me to suggest that it was remade in the middle of the 18th century, but it was still a playing instrument, and reconstructed in a later style which would not only give it more bass volume, but would allow, with the correct feet, the instrument to be free standing.

The presence, on the body of the Vienna instrument, of the brass hinges which are also to be seen on the other three instruments, would suggest that when the body was replaced, that it initially had the slotted pedals and stays, rather than pedal gates.

It would be interesting to see the bottom block, and ascertain if it was originally fitted with iron spike feet, but the pedal box obscures any evidence of these.

The stay hinges also show us that the E pedal was originally located in the centre of the middle stave, giving equally spaced pedals around the faceted curve of the soundbox and a cut pedal gate sits below the staved hinge.

The pedals for E and F have been relocated, requiring another pedal gate to be cut, and leaving one void, but the E and F pedals do not sit below the stay hinge, which would seem to imply that the pedal gates were cut after the pedal stays were removed, and divides the pedals into specific right and left groupings.

The pedal box is possibly the most confusing element of this instrument. Not only does it conceal evidence of feet and possible pedal studs ( the threaded stops that the pedals of French type pedals latch under) but it gives the instrument an appearance at odds whit how it would have looked originally.

The base of the pillar is bolted directly though the bottom block, with no receiving staple or ring required for instruments where the pedal rods run down the pillar.

There is no bevelled plate helping to hold the pedal box onto the face of the soundboard, and the bottom block sits flat on the top surface of the pedal box. It is screwed to the bottom block with 6 large screws (one missing) which show no signs of oxidation, which could imply that they are of much more recent date than the other metal work, or are made from, or plated with, a resistant metal. It is also fitted with 4 little wooden feet, which give the instrument great stability. Right the way through, though, to the late 1780s, far more usual are iron ‘spike’ feet. These can be driven into the wood of the instrument, as is the case in most German instruments, or made with plates that allow them to be screwed onto the bottom of the pedal box.

As already mentioned, the original E pedal is equipped with a cut pedal gate in the bottom block, but with no corresponding gate, allowing the horizontal movement required to latch the pedal in the pedal box.

This, coupled with the position of the gates for the E and F pedals where they are currently sited leads me to think that the gates were cut when the pedal stays were dispensed with, but before the pedal box was added.??What a modern harpist would regard as the B pedal has two notches cut into the body, neither corresponding directly with the original pedal-stay position, and only the one nearest the C pedal es equipped with a reciprocating notch in the pedal box. The result is that the ‘B’ pedal and E and F pedals have been shifted to correspond with later pedal positions, rather than being equally spaced around the bottom of the harp as the hinges indicate they had been previously.

On the harps that I have information for, the pedal disposition, left to right is actually B C D for the left foot, and E F G A for the right, with the B being the outermost pedal on the left. I have not been able to ascertain if the B pedal is like the other harps attributed to Hochbrucker, or, or is as would be expected on a French harp (with the D on the outside left) and the photographs taken by Wolf show the rods are certainly compromised, but this is far from conclusive.

The Zürich instrument has recesses in the bottom block that allow the pedals to run in slots, making them less liable to sideways motion if bumped when moving the instrument, which is always an issue in instruments that do not have folding pedals.

The folding pedals are not made to a pattern commonly seen. The brass tread is hinged via a slotted section that allows for the arc of folding the tread against the body, but supports the tread when in the horizontal position.

This next bit is difficult to write.

As already noted, the museum declined further examination of the instrument, or to supply more information of the known history. We do not know which are the replaced pedals, or when the pedal box was added. There are several other harps in the collection and four of them are in individual cases, allowing them to be walked around, and scrutinized. This instrument is placed in such a position, with another pedal harp immediately to its right, and a pair of keyboard instruments butted up to the side of the case it sits in, with directional lighting and projections on the wall opposite, making it difficult to see the instrument because of the reflections on the thick glass.

The case is labelled, on the front glass panel, with the label about mid-neck height, obscuring certain views, making it difficult to photograph the instrument, or to form clear views on how the harp has changed.

It is possible, though, to project some general ideas, which, whilst they cannot be proved without actual examination and discussion of the instrument, can at least begin to unpick some of the issues relating to the instrument itself, and the history of the pedal harp.

Firstly, looking at the comparative crudeness of the Vienna instrument compared with the other three, I do believe it was made in the first quarter of the 18th century.

I suggest that the body was rebuilt between 1750 and 1770, and that it was done to extend the playing life of the instrument, but after a new style of pedal harp had become common. I think that the board was found to be too thin, and braced, but without examination, it is difficult to say if this was done soon after the time of conversion, or to stabilize it at a later date. The foliate gilt decoration along the soundboard edges is far more typical of harp decoration after 1794 when ‘boxing’ along the edges of the sound board becomes common. The gilding does not show the characteristic wear patches where the players hands make contact.

I think the pedal latching system was changed, possibly because of loss or damage to a pedal stay, or because the French system had become accepted, and the stays were no longer needed.

The E and F pedals have been moved to make the pedals fit a more conventional layout, with pedals grouped for the left and right feet, rather than with the equally spaced curve indicated by the hinges for the pedal stays. This, again, would seem to post-date the French harp.

The pedal box is neither original to the instrument, nor was it in place before the E and F pedals were moved.

The pedals are at best adaptations of the original pedal arms, and are possibly later replacements. We know that three are not original, but we do not have a date for their reconstruction, or which pedals are reproduced.

The attribution to Hochbrucker is predicated to an inked label applied to the pedal box, which is not original. Dr. Beatrix Darmstädter posits, I understand on the suggestion of Beat Wolf, that the label was taken from inside the instrument, or the original bottom block, and moved to its current site. This raises the question of why anyone would feel the need to do that or why the other extant instruments to not carry similar labels?

Permission has not been granted to reproduce the photograph of the label, so I present a tracing of it. It appears, in the photograph to be on parchment or velum. The writing certainly could certainly have been written with a quill, but whilst it resembles Kurrent script, Sütterlin is not so very different, and the question is, if the label were removed from an earlier body when the replacement body was made, why would it be removed again to apply it to a pedal box added at a later date?

This is the only pedal instrument with a direct attribution to Hochbrucker. The other three, as far as I know, are attributed to Hochbrucker because the Vienna instrument is marked Hochbrucker.

I find myself wondering if it isn’t more likely that someone found a broken early pedal harp, and assumed it was Hochbrucker, and added the label, including the date of 1720 gleaned from written sources.

I would love to know if there are dates in the Zürich and Phoenix instruments, and if further evidence could be gleaned by examining the Vienna instrument.

I am very far from dismissing the Vienna instrument as a constructed instrument (there are harps like the Barberini and the Bologna chromatic harps that definitely seem to be composed of bits reassembled to create specimens) and still maintain it to be a very important instrument in the development of the pedal harp, but I would very much like to know which bits to believe, and would welcome discussion and input to try and create a clearer picture of the instrument as it was. I would be interested to receive other views, and, if possible, to encourage discussion with the museum.

© Mike Parker

2025-04-15